Mission Round Table vol. 11 no. 1 (January 2016): 10-16

Download this edition of Mission Round Table (2.5 MB)

Introduction

In 1993, after a dozen years of church planting and seminary teaching in Thailand, OMF leadership encouraged me to pursue a doctorate in inter-cultural education in order to advance my skills and give more credibility to the seminary program. The academic challenge was stimulating, yet my main desire was to use this opportunity to gain answers to recurring questions I had about the slow growth of the church. After 175 years of missionary presence in the country, Christians still made up less than 1% of the population. Seven years and more than 200 pages later I turned in my dissertation. I had hoped that my goal of adapting a Western teaching tool to the Thai context would be confirmed and adopted by the Thai. That dream never materialized. Even so, I gained a major insight into the learning style of my target people group—at their core the Thai were preferred oral learners.[1]

The weight of this discovery did not sink in until I attended a full five-day oral Bible story workshop in which no notes could be taken.[2] An opportunity to receive a certificate for completion of the course was offered on the last day by presenting a model story to the participants. Suffice to say, my feeble attempt at telling and unpacking an orally-told Bible story failed miserably and the certificate was withheld from my grasp—my literate paradigm was way too evident in my presentation. I took that workshop in 2006 and so, during the last decade, I have been on a quest to understand the world of the oral learner and just how best to incorporate oral strategies into discipleship and church planting in Thailand as well as broadly in Asia.

Up to that point I had taught the Thai with highly analytical methods based on a literate text paradigm. The subsequent paradigm shift was wrenching at times and was so significant that I chronicled my journey in an article entitled, “My Bumpy Road to Orality.”[3] What followed was a two-year span of time in which I traveled to nine Asian countries doing nothing but oral trainings. After such a broad exposure I can now echo the sentiments of Harry Box who concludes his book, Don’t Throw the Book at Them with these words:

The great majority of the people in the world today are oral communicators. This number includes many who have received some kind of literacy training or formal education, but who prefer to be oral communicators and so have not maintained their literacy skills. In spite of the extensive literacy programs as well as the formal and informal education systems around the world the number of oral communicators is steadily increasing. The highest percentage of oral communicators is in the developing countries of the world, which also have the highest percentage of people who have yet to receive a clear presentation of the Christian message.[4]

The great majority of Asian unreached people groups (UPGs) easily fit into the above description. With that in mind, the next question should be: How can we prepare disciplers and church planters who have been trained in highly literate methods to relate effectively with non-literate or preferred oral learners in cross-cultural contexts?

Primary and Secondary Orality

It is not difficult to make a case for a truly oral approach when referring to non-literates in UPGs. Concrete-relational, event orientated people gravitate towards holistic and oral communication. Pure illiterates, who can neither read nor write, need to start with the concrete and move to more abstract concepts. A minority of our world falls into this category and yet they should remain a priority target group as we seek to fulfill the Great Commission.

A much larger slice of the globe falls into the category of preferred oral learners (POL). Though they have had some education and have the ability to read, a lack of usage or incentive means that they end up as either functionally non-literate or semi-non-literate. The Lausanne paper, “Making Disciples of Oral Learners,” gives a helpful summary of the effects of such low literacy in the USA through an analysis of the National Adult Literacy Survey (NALS).[5] If half of American adults are in the lowest levels of literacy, what should we expect in the developing nations of Asia where there are fewer opportunities for education?

Harry Box highlights for us the differences in literate learners and oral learners, whether primary or preferred:

There is a marked contrast between the worldview characteristics of oral communicators and literacy- oriented people. This is not simply at a superficial, surface level, but rather at a deep worldview level and is particularly significant in the whole area of communication. To move from an oral worldview position to a literacy-oriented worldview position, or vice versa, requires a major worldview shift.[6]

Such a shift is no less needed for a group which we increasingly encounter in our media saturated age—secondary oral learners. With the advent of the internet and a multitude of readily accessible electronic devices we have ended up with a postmodern generation of browsers and scanners who spend most of their day viewing various screens replete with pull down menus, video clips with highly kinetic, visual as well as sensory graphics. This digit-oral generation is increasingly replacing the written word with audio clips, television, virtual reality, and social media. Media producers recognize that we are all hard-wired to stories, which is why you see a proliferation of narrative genre on YouTube, television sitcoms, and the standard fare we find in movies. My daughter’s college roommate well illustrates the connection between young people and screen-sourced narratives as she watched ninety movies during a ninety-day span over one summer.

The cumulative effect of such massive doses of media is reflected in the declining reading habits of the American adult population of which nearly a quarter had not even read one book during the past year.[7] If reading habits in the West are declining at such a rate, one can only imagine where developing nations will end up as this electronic media trend continues.

Not a Silver Bullet

Orality, perceived as a new trend in missions, generates valid concerns which need to be addressed. There has been a tendency to hype the movement by making extravagant claims of its effectiveness. The result is that oral zealots end up being accused of denigrating the need for literacy. Yet being literate is of great advantage for any believer and we should long that quality literacy training and literature be made availabe for all the UPGs of the world. However, the reality is that there remain four billion oral communicators in our world who can’t, don’t, or won’t process new information by literate means.[8] We have done an admirable job in reaching the more literate populations of the world, which is why concentrating more effort in reaching the preferred oral learners is so crucial.

We should not view the use of literacy and orality as “either-or,” but “both- and.” A master carpenter needs a variety of tools in his tool belt. Traditionally, the communication tool belt of educators and trainers in Asia has been weighted with text-dominated literate tools emphasizing western theology, propositional truths, and linear/logical thought processes. We will always need such tools, especially when we are covering the details and principles of the Word found in epistolary or more didactic genres. Different genres require different tools so that God’s word can be interpreted, applied, and communicated properly. Paul was careful to teach “the whole counsel of God” in various ways (Acts 20:27). His example reminds us that propositional truths and narrative stories need each other.

Jesus modeled balance in his communication, using both sermonic discourses as well as numerous stories. There were times when he taught in a more direct propositional manner, yet the bulk of his teaching was parabolic as seen by the parables in the Gospel of Luke which make up more than half of the book. J. M. Price observes, “Undoubtedly the distinctive method used by the Master was the parable or story. It stands out more prominently in his teaching than any other.”[9] Matthew’s Gospel states, “All these things Jesus said to the crowds in parable, indeed he said nothing to them without a parable” (13:34). Jesus was a master communicator and as such consistently packaged truth in a story form for use with non-literates as well as highly educated Jewish leaders.

Our strong suit as missionaries has always been literate tools and I expect them to predominate on into the future. We all appreciate the massive effort expended over the centuries to produce and preserve the printed Bible and all of the resources related to it. Yet in the process we seem to have depreciated the Bible in oral forms and have failed to adequately meet the needs of the majority that do not prefer the printed page.

Bringing Stories to Life

Oral cultures are experiential, sensory, and holistic in nature. Oral learners flesh out meaning, rather than trying to explain it abstractly or logically. Different cultures gravitate to different art forms. Whatever the art form, it is important to make sure that they supplement and support the core of the teaching, which is the Bible story itself.

Contextualized Songs, Poems, and Chants

Songs have a phenomenal sticking power and can be retained over decades. Understandable and contextualized songs can work in tandem with the story to seal the message to both the heart and mind of the hearer. Avery Willis had his trainees tell the story, dialogue about it, act it out, and finally work on creating a song, since “Music touches the emotions. If you are involved in creating a song, you will likely remember the story better. If the song has a catchy tune, you will sing it during the following week, and it will help you recall the main point of the story.”[10] Certain cultures are particularly touched by poetry. An example of this comes from Russia where I witnessed a young girl recite a very long biblically-themed poem from the pulpit, totally from memory. In Thai culture chanting is a common form which I have made use of in church by having the whole congregation recite key phrases after me. Since this is a practice they have all utilized since childhood it is easy for them to transfer the practice to church.

Drama and Dance

John Davis portrays drama as the communication key for the Thai. “To effectively communicate the message it needs to be packaged in a medium that will be culturally acceptable. For Thai this medium is drama. There seems to be no other means of communication which makes such a powerful impact on Thai audiences as the dramatic arts.”[11] The Thai use their innate acting talents in both drama and music in an entertainment form using extravagant costumes and improvisation called Likay.[12]

This tendency to improvise extends to dramas performed in church, so that in our story training we have resorted to having a single narrator tell the story slowly as the drama troupe performs the story through a silent pantomime. In this way the story is clearly featured, rather than trying to have the actors memorize their lines, which can easily degenerate into a comedy routine that may blur the story line. The Thai are also graceful and expressive dancers, especially with their hands. Many churches use this natural gifting during festival times and special dates in the Christian calendar.

Proverbs and Cultural Stories

Like most Asian cultures, Thailand is replete with proverbs and pithy sayings, many of which have similar meanings to biblical proverbs. Such succinct adages are easily remembered and can be easily incorporated into evangelism and discipleship. Since the majority of Thai are Buddhist, it is helpful to be familiar with a few religious stories, which can be used as bridges in pre-evangelism. In the book, From Buddha to Jesus, Cioccolanti suggests familiarity with stories like “The Blind Turtle” and others to show the relation of sin to karma.[13]

Art and Object Lessons

It has been said that “A picture is worth a thousand words; a story is worth a thousand pictures.” Stylistic drawings with Christian themes have been used effectively to build bridges of communication with Buddhists in Thailand. There are full sets of such drawings based on Bible story sets.[14] I personally like a more biblically accurate set developed by the Southern Baptists in the Philippines.[15] A missionary I know takes fellow artists to a university campus and as the artists set up their easels and draw biblical scenes, he tells the story being drawn to Thai onlookers. A creative use of object lessons can also supplementa story. I have cut out of cardboard a simple four piece object lesson which I have used with over 1,000 people as I tell the paralytic story of Mark 2:1–12. The construction and a demonstration of how to use this tool can be found on the internet.[16]

Media

Creative approaches to oral communication are virtually endless in this age of apps, Bluetooth, micro SD cards, movie CDs, VDO clips, and easily accessible electronic devices. The “Jesus” movie, with over six billion showings world-wide, is a prime example of the potential of media’s global impact.[17] For a fuller treatment of the broader redemptive meta-narrative, there are full-length eighty-minute videos like “The Hope”[18] or “God’s Story”[19] which has been produced in 300 languages in eighty countries. In Thailand I purchase “God’s Story” cheaply in lots of a thousand in order to give them out to interested Thai during festivals like Christmas. Such meta-narratives lay out a sound redemptive story line into which the individual stories of the Bible can be inserted.

A gospel poster formerly used widely in China. China’s Millions (July 1936): 131. Panel A: Neither the bald Buddhist priest, nor the Taoist can reach the sinner sinking in the mire. Panel B: The Confucian teacher cannot help him up. Panel C: Evangelist stoops down and lifts him out of the horrible pit and sets his feet upon the rock. Panel D: A new song is put into his mouth. “Many shall see it and fear, and shall trust in the Lord.”

Story Sets

One needs wisdom when selecting stories, since there are around one thousand Bible stories to choose from. A comprehensive set covering key Old and New Testament stories could number upwards of two hundred, while a more manageable set of core stories can be reduced to around thirty. Evangelizing and church planting in a culturally sensitive way means that story-set selection should take into account key world-view issues, bridges, and barriers.

I have found that shorter stories of ten to fifteen verses with limited dialogue and action elements are best for initial training of story-tellers. There is a place for crafting a story when summarizing longer sections or with Unengaged People Groups, a process championed by One Story training.[20] However, there is much to be said for learning a Bible story with content accuracy, yet allowing it to be expressed with natural wording, rather than rote memorizing of the text, a practice which slows the learning of a story.

Story and Discipleship/ Church Planting

Oral methods of communication play a vital role, not only in the initial planting of churches, but also in the ongoing nurture of church planting movements. We will see that it is possible to incorporate oral elements into most all aspects of evangelism and church life among oral peoples.

Preaching

C. Sproul is an unusually systematic and propositional pulpiteer, who sees the value of narrative preaching. “I’m big on preaching from the narratives because people will listen ten times as hard to a story as they will to an abstract lesson.”[21]Like Sproul, the ex- pat and national workers I encounter see the benefits of stories, but mainly with youth, in small groups, or in evangelism rather than with adults on Sunday morning. Homiletically they see stories primarily as illustrations for the major points in their sermons, rather than acting as the core subject of their message.

Describing an “oral sermon” as a narrative sermon helps clarify the intent, but narrative sermons often maintain a heavy literate focus. To create an oral atmosphere, I typically rearrange the chairs into a semi-circle and then, stepping down from the pulpit, I give a short introduction to the story with a closed Bible and then, as I open the Bible, begin to tell the story accurately, yet in a natural way. As I close the Bible I ask the congregation to get into pairs and repeat as much as they remember to their neighbor (in more seasoned congregations you can have one person volunteer). Next, I lead them through the story once more in a participatory way, which brings me to about the fifteen-minute mark in my sermon. The remaining time is the core of the sermon as I unpack the story using open-ended observational questions, which the congregation responds to. Near the conclusion of the message, I move to application questions based on the biblical principles and lessons the congregation discovered as they made observations within the story. What you end up with is an engaging and often riveting inductive study of flesh and blood characters with the added benefit of placing a powerful narrative in the heart pocket for future retelling.

Many audiences are very used to a literate paradigm and need to be educated in such an oral approach. For this reason a preacher may want to read the story as well as tell it and instead of direct questions to the congregation, may simply use rhetorical questions, which he can answer himself (at least the congregation has a moment to reflect on the question and form their own answer, albeit silently).

Small Groups

One of the best disciple-making environments and a key to spiritual maturity are small groups that incorporate the best practices of worship, “one-anothering,” and inductive Bible study with a view to obedience and outreach. Avery Willis believed strongly in preaching and taught it in seminary, yet he made this statement about the power of small groups:

You don’t make disciples through preaching. Trying to make disciples through preaching is like spraying milk over a nursery full of screaming babies just hoping some of it falls into their mouths. That is about all you are doing when you are preaching. You make disciples as Jesus did—in face- to-face relationships in small groups.[22]

Most people associate serious inductive Bible study with extensive note taking and a detailed focus on the printed text. There is usually one expert facilitator that everyone looks to as their authority. In an inductive Bible study oral style, everyone is on a level playing field as they learn the story together and use observational questions to unpack the story, being careful not to stray outside the bounds of the narrative. Everyone can contribute to the discussion, which allows each member to have the joy of personal discovery of truth. Participants begin to identify deeply with these life and blood characters and end up making deeply penetrating observations of their lives and more importantly, gain new insight into the attributes and workings of God.

Key components of such clusters is having each member identify both an obedience action step as well as identifying a person to tell the story to in the coming week. It is very satisfying to hear members describe how they applied the story during the week and experiences they had as they shared it in the community. This accountability aspect of obedience and sharing the story fills in a weak point that many have observed in traditional small groups. As the group grows and members learn quickly how to lead the group themselves, they are encouraged to start their own groups, thus passing on the DNA of the group in a replicable way.

Church Camps

I have had the privilege of speaking at Thai church camps where the messages were all orally told Bible stories. An added advantage of this approach is that children from around 10–12 years old and upwards can stay with their parents during the teaching sessions. The traditional church camp separates out the older children and often teaches them a curriculum unrelated to what the adults receive. One of my greatest joys is seeing families sitting together to both worship and unpack stories together, then at meal times to see that momentum is carried on as parts of the story are discussed around the table.

Family Devotions/Personal Quiet Times

Deuteronomy 6 begins with the famous Shema (verse 4) and continues with an admonition for families to meditate on God’s Word as a life style (verses 7–9). In verses 20–24 a father is told what to do when his son asks the meaning of the 613 commands found in the Torah. To grasp even a portion of those commands is a daunting task for priests, much less children. The answer is not to explain the meaning of individual verses, but in effect to tell one’s son the epic stories of the exodus, wilderness wanderings, and conquest of Canaan. As a child grows the details of God’s law will need further explanation, but a parent’s first priority is to make sure his or her child is well versed in the redemptive stories of the Bible.

Once a home schooling couple asked me if they could bring their two Junior High aged children to our five-day Simply the Story training. I readily agreed and was not surprised when these sharp MKs exceeded many adults in their grasp of the process. On the last day the father thanked me for the church planting applications he had gleaned during the week, but was most enthusiastic about the potential he had already seen for family devotions. Instead of dominating the devotional times and relying on printed materials, the parents could allow their two children to lead the devotions in an oral style using stories relevant to their family needs. A Bible professor confided in me that in the past he had difficulty discussing the Bible with his wife because of her perceived inadequacies against his vast theological knowledge. However, when they concentrated on inductive study of stories, they found it very natural to discuss God’s word together as they sat at home, in a restaurant, or even on trips in the car.

Counseling

Harriet Hill, working among traumatized Africans, found that one of the most effective ways to counsel these oral people was through sharing stories of abuse and trauma that they could readily identify with.[23] The nature of our world means that wounds of the heart from war, ethnic tensions, natural disasters, and abuse will only increase. Bible stories address the full gamut of human needs and many are brutally honest accounts of the problems and traumas that mankind faces on a daily basis. The field of counseling is quite broad and complex and there is always a need for professionally trained counselors. However, most oral populations do not have the luxury of licensed counselors and must rely on pastoral counselors. A lay counselor with a database of biblical stories that address felt needs can discern the need being presented and share a story that addresses that need.

Short Term Mission Trips

Most fields accept a large number of short term mission trips each year. I try to make sure that each member of the groups I receive or prepare for such trips is ready to share at least one Bible story orally. I try to select a good cross section of stories that have a good potential for use on the trip. A team of nine visited me for two weeks and because each one was prepared to tell their story in English, I was able to size up the ministry situation and use a number of their stories. Those who never told their stories on the field were at least able to gain personal benefit, plus the ability to use their story at a future time.

Seminary and Christian Schools

All of my academic training through the PhD level occurred in the literature-saturated west, so it was no surprise that I taught as I had been taught. I never seriously considered narrative or oral communication techniques due to my propositional bias. I unconsciously believed that “real truth” was best packaged in a propositional package and that somehow using Bible stories would miss the main point that I was trying to make.

Presently I am experimenting with teaching seminary classes in a much more oral manner by stressing stories and characters along with doctrine. This approach has been well received by a number of seminaries in both Asia and the States. In Thailand, my desire for this approach has been fueled by the realization that most of my graduate students are effectively biblically illiterate, having missed an exposure to many foundational stories that I learned as a child in Sunday School.

By modeling what I call “oral andragogy”[24] in the classroom and designing oral exams, projects, and presentations for the students, I am seeing a positive absorption of class content, but also a noticeably higher engagement and enjoyment of God’s Word on the part of the students. Such an innovative approach, however, often ends up being a concern to other faculty leaders. To at least partially ease the fears of these “gatekeepers” of institutions, I wrote an article entitled “Objections and Benefits to an Oral Strategy for Bible Study and Teaching.”[25] It is important to prove through qualitative research, demonstrable results, and transformational impact the validity of any perceived new training approach. That is why more practice and evaluation of oral approaches in academia is needed before any measurable influence will be seen in traditional theological education.

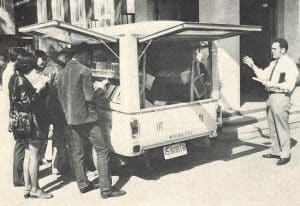

As the Taiwan Field Literature Representative, Siegfried Glaw used a bookmobile to sell Bibles and other Christian literature in the 1970s. East Asia’s Millions (June 1974): 56.

Bible Memory

Most every Christian has benefitted from memorizing a verse pack of key Scriptures. The advantages of such a discipline are readily seen, yet most would admit that they have forgotten many of the verses they memorized for want of a disciplined review system. I have found that the requirement of saying the verse word perfect and repeating the precise chapter and verse to be daunting for many. I first took up this formidable task in seminary when a fellow student challenged me to memorize two key verses from each book of the Bible, a total of 132 verses. I’ve benefited greatly from this exercise and have no need to review many of them, however, certain verses need constant review after even forty years.

You can imagine my amazement after a fairly short exposure to learning and absorbing Bible stories, to see the number of verses in my heart pocket far exceed the 132 individual verses in

my verse pack. Up to that point I could not have told you even one content accurate Bible story. (I could have summarized a number, but unlike my verse pack, my value system for stories did not include content accuracy.)

Since only a few of the stories I’m working on exceed the ten to fifteen verse limit, I find that simple repetitions coupled with picturing the story with a drawn storyboard places a high percentage of the story into my long term memory. The added benefit over time and practice means that many stories need virtually no review, a luxury I never had with my verse pack. Just working on ten stories of ten verses each means that you have potential ownership of one hundred verses, a figure that any church planter or pastor would love to claim for his congregation.

English Teaching

The ten members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) have agreed to use English as the medium for business.[26] As in other Asian nations, church planters are finding that the teaching of English is becoming an increasingly effective bridge builder in relationships and sharing the gospel. Gary and Evelyn Harthcock found this to be the case in their ministry in Cambodia to Buddhist monks and ended up producing a number of resources for ESL teaching.[27] Recently our team of story-tellers in Chiang Mai was asked to teach medical students conversational English in a story form. Following the Harthcock’s examples, simple, short Bible stories will be used as the basis for the lessons. The students will first learn the story in a group context and then dialogue about the characters and events as they respond to open-ended questions along with an emphasis on difficult vocabulary and wording.

Oral Bible Schools

The nature of Bible education on the field has always been geared to literate learners, which means primary oral learners have had great difficulty in getting the training they need. For instance, usually literacy is a minimum requirement for the role of elder. However, the requirement in 1 Timothy 3:2 states that one be “apt to teach,” a stipulation that can be met if the elder gains a good grasp of the Bible in oral form and knows how to communicate it orally. An encouraging trend in training such leaders has been the development of Oral Bible Schools (OBS), which have been started in places like India, Africa, and the Philippines.

One effective model is to have the students meet for a two week period as they learn fifteen to twenty stories which they practice and then take back to their villages for the next two weeks where they share the stories and work at their occupation.[28] This process continues for six months and gives students a good grasp of over 200 Bible stories. The goal is to encourage these students to continue learning and gain as much literacy as they can so that they can accurately handle the more propositional genres of the Word. However, the reality is that many will remain non-literate or functionally so.

Conclusion

Like most of my missionary peers, I am a “high end user” of the Bible and am used to processing God’s word with highly literate tools. At the same time, like my peers, I find myself working among “low end users” who, as preferred oral learners, process information much differently than myself. Missiologically we have done an admirable job in reaching the relatively small percentage of the world’s population that are strongly literate, but that leaves billions both in the majority world as well as the secondarily oral West who respond best to an oral approach.

Recognizing and accepting the major differences in literate and oral communication/learning styles is a necessary first step in addressing this issue. One should expect some discomfort as adjustments are made and cherished literate paradigms are challenged. Missiologically the oral movement is relatively new and is still developing as various trainers seek to find best practices in orality. More qualitative research and longitudinal studies of the impact of such training needs to be done. Also, the biblical and academic validity of an oral approach needs to be confirmed and barriers need to be surmounted if the “gatekeepers” (educators, denominational, and mission agency leaders) are to be affected.[29]

It seems fitting to end this article with the challenge that pastor Andy Stanley gives to those who seek to preach effectively to this present generation in a style that is quite different than his famous father, Charles Stanley. Andy’s appeal is specifically to preachers in western contexts, yet a similar challenge could be given to missionaries ministering to oral populations:

Are you willing to abandon a style, an approach, a system that was designed in another era for a culture that no longer exists? Are you willing to step out of your comfort zone in order to step into the lives God has placed in your care? Are you willing to make the adjustment? Will you consider letting go of your alliterations and acrostics and three point outlines and talk to people in terms they understand? Will you communicate for life change?[30]

[1] John Davis, Poles Apart? Contextualizing the Gospel (Bangkok: Kanok Bannasan, 1993), 143.

[2] Simply the Story is a story training organization based in Hemet, California with the distinctive of training storytellers to dig deeply and inductively into Bible stories in an oral style. STS offers workshops in six major regions of the world and has been used in over 100 countries with the “God’s Story” DVD being translated into 335 languages.

[3] Larry Dinkins, “My Bumpy Road to Orality,” http://www.simplythestory.org/downloads/PDFs/ MyBumpyRoadToOrality.pdf/ (accessed 4 December 2015).

[4] Harry Box, Don’t Throw the Book at Them (Pasadena: William Carey, 2014), 189.

[5] “Making Disciples of Oral Learners,” Lausanne Occasional Paper 54 (October 2004), 18, https://www.lausanne.org/ docs/2004forum/LOP54_IG25.pdf (accessed 8 December 2015).

[6] Harry Box, “Communicating Christianity to Oral, Event-Oriented People” (DMiss diss., Fuller Theological Seminary, 1992), 59.

[7] “The Decline of the American Book Lover,” http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2014/01/the-decline-of-the-american-book-lover/283222/ (accessed 4 December 2015).

[8] “Making Disciples of Oral Learners,” 3.

[9] J. M. Price, Jesus the Teacher (Nashville: Sunday School Board of the Southern Baptist Convention, 1946), 99.

[10] Avery Willis and Mark Snowden, Truth that Sticks: How to Communicate Velcro Truth in a Teflon World (Colorado Springs: NavPress, 2010), 95.

[11] Davis, Poles Apart?, 114.

[12] “Likay,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Likay/ (accessed 4 December 2015).

[13] Steve Cioccolanti, From Buddha to Jesus (Oxford: Monarch, 2007), 123–32.

[14] Sawai Chinnawong and Paul H. Deneui, The Man Who Came to Us (Pasadena: William Carey, 2010).

[15] Caloy Gabuco, Telling the Story:Chronological Bible Story Pictures (Paranaque City, Philippines: Church Strengthening Ministry, 2003).

[16] See http://www.chiang-mai-orality.net (accessed 11 December 2015).

[17] See http:/ www.jesusfilm.org/aboutus/history (accessed 11 December 2015).

[18] See http://www.thehopeproject.com/en (accessed 11 December 2015).

[19] See http://www.gods-story.org (accessed 11 December 2015).

[20] See http://onestory.org (accessed 11 December 2015).

[21] Steven Matthewson, The Art of Preaching Old Testament Narrative (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2008), 20.

[22] Willis and Snowden, Truth that Sticks,” 87.

[23] Harriet Hill, “Healing the Wounds of Trauma: How the Church Can Help,” Podcast recorded on Story4All, http: // story4all.libsyn.com/s4a048-healing-wounds-through-storying (accessed 8 December 2015).

[24] Andragogy, takes the Greek word andra meaning “man” and combines it with agogus meaning “leader of” to stress the teaching of adults. This is an important distinction, since many people think of telling stories as an approach most suited for children.

[25] Larry Dinkins, “Objections and Benefits to an Oral Strategy for Bible Study and Teaching,” William Carey International Development Journal 2 (Spring 2013): 11-17.

[26] “Wall Street English Prepares You to Get Ready for AEC 2015,” http://www.wallstreetenglish.in.th/wall-street-english/aec/?lang=en/ (accessed 4 December 2015).

[27] See http://pages.suddenlink.net/eslbiblestories/index.htm (accessed 11 December 2015).

[28] “Oral Bible Schools,” http://simplythestory.org/oralbiblestories/index.php/oral-schools.html (accessed 4 December 2015).

[29] Larry Dinkins, “Objections and Benefits to an Oral Strategy,” 11–17.

[30] Andy Stanley, Communicating for a Change: Seven Keys to Irresistible Communication (Portland: Multnomah, 2006), 90.